Something happens to me when I travel – especially when I travel for business. I am in a hurry. I am in a hurry to get there, and in a hurry to get home. Anything that detracts from this mission, such as the person in front of me who can’t grasp the simple rules at the TSA pre-check, the person with four large suitcases who is delaying the departure of the rental car bus, the person in front of me at the hotel check-in who is asking the front desk agent for a comprehensive review of all nearby restaurants and their menus – I could go on. And God save your soul if you are the unlucky one delivering the news that, “We are out of cars right now,” or “You’ve been randomly selected…”

Two days ago, after I mindlessly left my roller bag on the rental car bus because I was on a phone call and had to wait for the bus to come back around, I was walking from the parking lot into the hotel at what some of my in-laws refer to as the “Krause pace.” I barely noticed the man sitting in a wheelchair on the front drive sidewalk as I blew through the revolving door into the lobby. I always notice someone in a wheelchair, but it is more like the way a wild animal notices a person in a car and considers the two together to be just one big thing. I notice someone in a wheelchair, but I don’t notice the someone who is in the wheelchair. I don’t notice this especially if I am in a rush.

Well, because I had been in a rush, I had an extra forty-five minutes before I needed to meet my colleagues for dinner. That was too much time to sit around and not enough time to go to the gym. So, naturally, I went to the bar. Just as I was squeezing the lime into my “club soda,” the wheelchair bundle rolled up next to me and said, “Do you mind if I squeeze in here?”

Now, I am an introvert. If I could complete an entire business trip without talking to a single person I don’t already know, I would consider the trip to be a success. Give me an app, a few kiosks, and my “don’t talk to me on the plane” AirPods and I am all set. I already know everyone I like.

“Sure, no problem,” I said. We shook hands.

“Paul,” he said.

“Tim,” I replied. “Nice to meet you, Paul.”

His grip was weak, and I noted that he handled his drink with his left hand.

This is usually the last moment I remember someone’s name. Anyway, I thought I struck the right tone. I sounded convincing enough to avoid seeming rude, but not so convincing that he thought I was inviting an actual conversation. “So, what brings you to town?” he asked. And thusly it began.

Paul was in town to receive stem cell injections to his spinal column. This piqued my interest, because I try to keep up with progress in stem cell research especially as it applies to healing potential in spinal cord injury. I pressed, explaining my personal interest in the topic, at the highest possible level. I had a son and he was injured – that’s it. Paul had had two treatments so far with no results.

“So, did you break your neck?” I asked.

“Yes,” he said. “Three years ago.”

“What happened?” I asked. “Did you fall off a roof or hit a tree skiing?”

“No.” He conceded. He paused briefly to purse his lips and shove them into his right cheek. He went on. “Nothing that interesting. I was walking through my living room, tripped, and hit the coffee table with my chin. My neck snapped back. It broke my C2 vertebra.” (C2 is the second one down from where your head hooks to your body, so damaging your spine there pretty much screws up everything.)

He returned with, “How about your son?”

“Mountain biking. C4 to C6”

Every conversation between two people impacted by SCI starts this way. It’s instead of showing a passport.

“Can you walk?” I asked.

“Yes, a little, but I don’t have much stamina,” he answered.

I launched into Theo’s story, careful to point out that learning to walk again turned out to be just the beginning of his battle. I have developed a reasonably concise pitch by now, and occasionally Paul interrupted with a “Wow,” or “That’s inspiring,” especially when I mentioned Theo was able to snowboard again.

Paul seemed particularly focused as I went on to explain how Theo had battled depression and thoughts of suicide. “And where is he today?” Almost apologetically, I explained how well Theo functioned independently and that he was living in DC, although there was plenty he couldn’t do. Paul pushed. Paul, forty-eight years old, requires constant care. His wife is the sole care-giver.

Paul’s eyes widened, and he sat straighter in his chair as I described some of Theo’s lingering limitations, and Paul shared his own. Just then he froze, his shoulders hunched and drew sharply in to his neck, and his eyes glazed. The searing shot of nerve pain, a common by-product of spinal cord injury called neuropathy, took his breath away as it enveloped his entire body. Five or ten seconds went by before he was able to recompose himself.

“Wow,” I finally said. “Do you take something for that?”

“I used to, up until about a year ago. Percocet – Lyrica – everything. Now it’s just Tylenol.”

“Why did you stop?”

“I decided it was better to feel everything than to feel nothing.”

“Ironic,” I thought to myself as I glanced down at my almost empty glass.

Realizing I was now late to meet my colleagues for dinner, I began to excuse myself. I slurped the last watery sip, and I was just pushing back the stool when Paul said, “Mr. Krause, I have been having some of the same thoughts as your son. My walking is actually getting worse, not better, and it’s very frustrating. I used to be the operations director for Outback Steakhouse and was always active. Until I met you tonight, I’ve been seriously considering whether I want to continue to work at it, or just let it all go. But your story has inspired me. I want you to know that you have changed my life today.” Now I was the one doing the recomposing for the next five or ten seconds.

At this moment, you may think I told you this story so that you could be impressed that I had changed someone’s life – that I had done something special and you would click the “Wow” face instead of only the “Like” button on this post. I’ve thought about that for two days before finally deciding to post this.

Paul continued: “Yesterday a pastor was sitting here.” (I smiled at that one.) “Today, it was you. Between the two of you, I feel like God is trying to tell me something. I believe He brought us together for a reason.”

“God may not be finished with you,” is about all I could come up with. After all, I was just there to waste forty-five minutes. But, unable to leave it completely alone, I continued: “Maybe you need to see this through. If you do, you might end up somewhere you never expected, doing something more fulfilling than you ever dreamed. Imagine the story you would have. Someone might need to hear that story.”

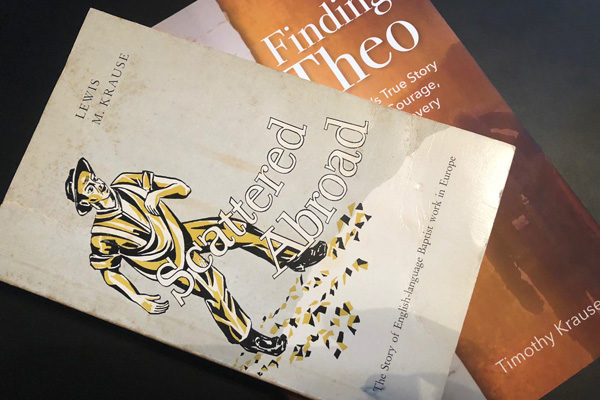

Here is the thing. I didn’t do anything special. In fact, I did everything possible to avoid doing anything special. Ultimately, I just told my story to another person. Everybody has a story, and someone needs to hear it. If you tell someone your story, they might tell you their story and that might be just what you need to hear at that moment. I think that’s the stuff of miracles. When Paul rolled up to my side, he didn’t know I had spent two hours that afternoon walking around Craig Hospital in Denver, a place that stores some difficult memories for my family. I know I will never forget Paul’s name.